Writers: Melanie Manchot and Leigh Campbell

Director: Melanie Manchot

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Lying in the archives of the British Film Institute is a groundbreaking 1901 crime thriller set in Liverpool. Normally, its existence may only be of interest to cinema historians, but it now provides the inspiration for director Melanie Menchot’s new film within a film.

On one level, Stephen is an account of the devastating effects of addictions in a working class community. On another level, it is a penetrating study of the craft of film acting. Maybe the two levels do not always connect cleanly, but this 78-minute drams proves to be consistently intriguing.

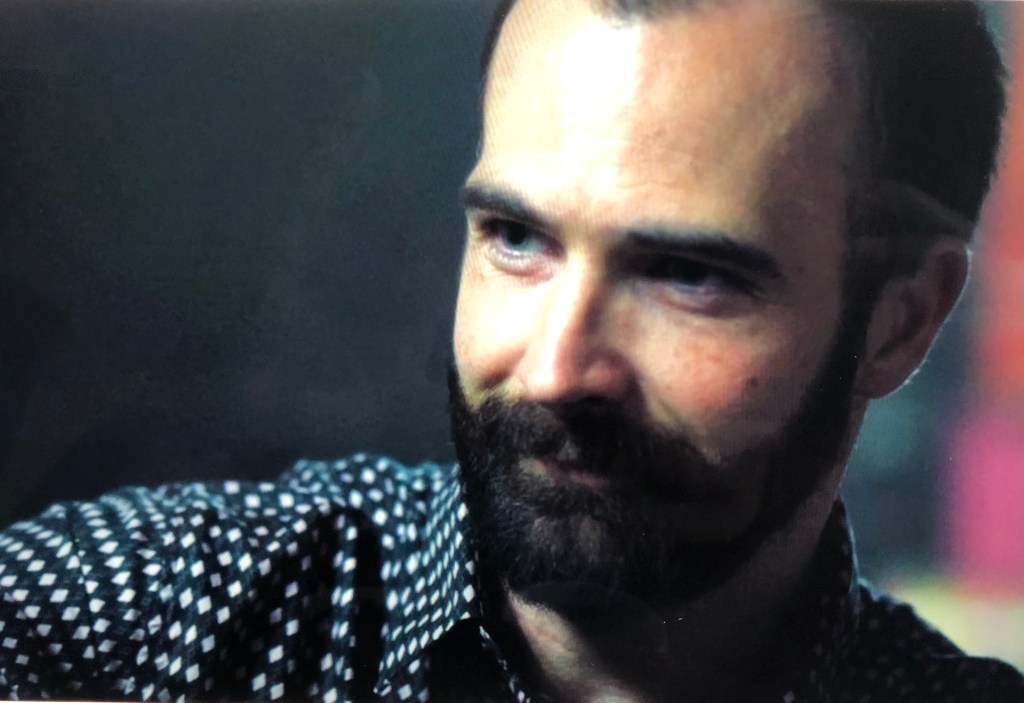

Actor Stephen Giddings stands before a casting panel, auditioning for the central role of Thomas Goudie in the 1901 film. Taking method acting techniques to extremes, he immerses himself in the role, experiencing addictions to gambling, alcohol and drugs and mixing with real life addicts who play themselves in the film. The labyrinthine narrative structure, merging past with present, fact with fiction, comes to mirror ways of life from which there is no easy escape.

Menchot offers little help to audiences trying to wade through the complexities. There are no period costumes and the locations are all modern day. Areas of Liverpool that tourists are least likely to visit are captured in cinematography that is in cold and unwelcoming, underlining the key point that that addiction problems can strike the lest privileged and most vulnerable in society.

Giddings binds the film together sturdily, expressions of hopelessness on his face as he becomes Goudie, falling victim to forces beyond his control and facing up to the mental health problems that addictions bring. He leads a group of actors, mostly little known, with the exception of former soap star Michelle Collins, who is cast against type as a menacing loan shark. Her brief contributions send shivers down the spine. The appearance of non-professional actors in scenes, such as those set in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, adds valuable authenticity to the drama.

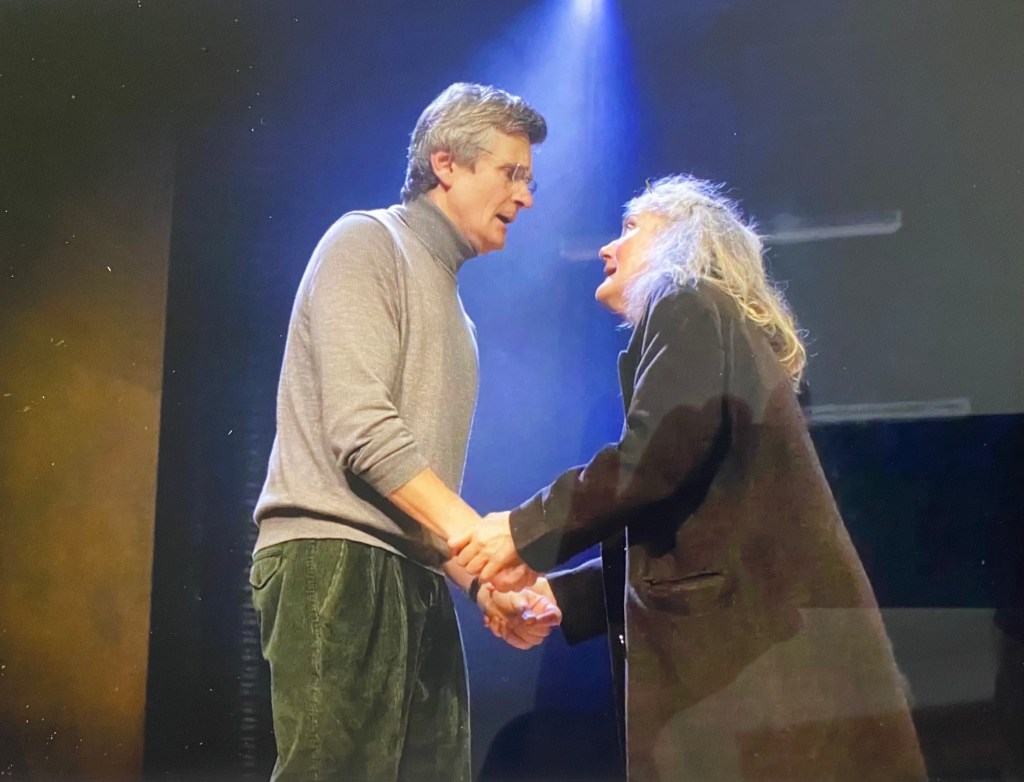

Manchot’s unorthodox approach pays dividends, but it also draws its toll, as moments of truth are revealed abruptly to be moments of deception. If we are to invest fully in these characters, their emotions and their dilemmas, we need to believe in them and repeated reminders that they are actors on a film set that is itself on a film set prove to be counter-productive. Particularly frustrating is a potentially moving scene in which Stephen/Thomas meets his brother (Kent Riley) in a pub, the latter trying trying to persuade him to mend his ways for the sake of a loving family. The emotional power builds, but then the camera pull out and it all mets away.

Stephen is bold in style and harrowing in content, but, in places, its complex structure softens its impact.