At first sight, a Broadway musical dealing with mental illness and bereavement is far from normal. Yet, as director Michael Longhurst points out, many of the greatest musicals cover very dark themes and a song can be more effective than a paragraph of words in exploring the human condition.

Longhurst was chairing a discussion among cast and creatives on the stage of Wyndham’s Theatre in London’s West End, to where his critically-acclaimed 2023 production of Next to Normal at the Donmar Warehouse is transferring. The group sat scattered around a nondescript family kitchen, being the solitary set on which all the drama unfolds.

The show’s American composer, Tom Kitt, reflected on the 26-year journey that has brought him here. It all started when he and book writer and lyricist, Brian Yorkey, were challenged to write a 10-minute musical. He cites Stephen Sondheim and Kander and Ebb as his main influences, being writers who are not afraid to delve into serious issues nor to venture through previously unexplored territory. The development of Next to Normal led to an off-Broadway premiere in 2008, transferring to Broadway in 2009, picking up a Tony Award for Best Original score and a Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Now, Kitt roams daily around London’s theatre district, looking in wonder as he realises that he is becoming part of it all.

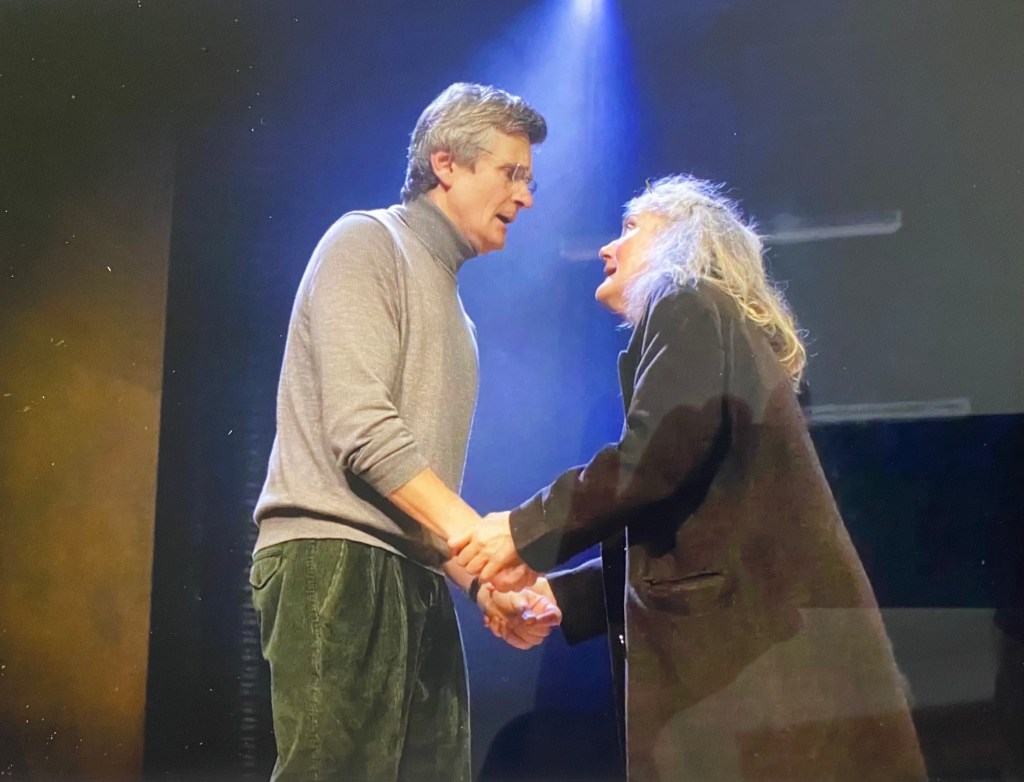

During the 15 years or so that it has taken for the show to cross the Atlantic, it developed something of a cult status here, fuelled by clips on the internet. One avid fan was actor Jack Wolfe, who had bought tickets for the Donmar Warehouse before auditioning for the key role of Gabe. He got the part and, with it, the show-stopping song, I’m Alive. When reading the script, Longhurst recalls that he kept hearing the voice of American actor Caissie Levy as Diana, the troubled wife and mother. He had directed her in the New York production of Caroline, or Change and, happily, she accepted the role, which she is now reprising.

The intimate Donmar Warehouse has around 200 seats and is configured so that the audience is almost sitting in Diana’s kitchen. Longhurst talked about the challenges of transferring his production to a medium-sized, traditional proscenium arch theatre. Olivier Award-winning actor, Jamie Parker, who plays Diane’s husband Dan, has starred in musicals at many West End and London fringe venues and he believes that this transfer gives the show the chance to exercise its muscles. He says that, through rehearsals and previews, the actors have been finding new dimensions for their characters and in the story.

With the costs of staging extravagant new musicals spiralling upward, risk-averse producers on Broadway and in the West End seem to be turning either to safe bets or to smaller scale, more intimate shows. Maybe Next to Normal is confirming a trend towards what is becoming the new normal.