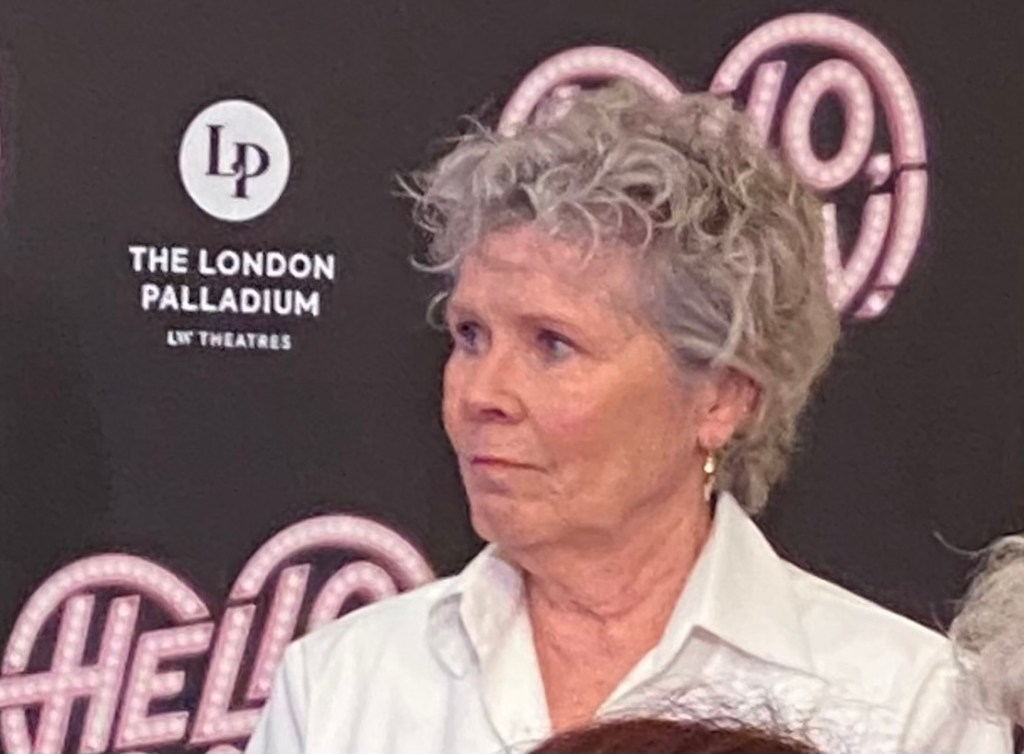

Photo: Steve Gregson

Writer: Noël Coward

Director: Tom Littler

⭐️⭐️⭐️

By 1966, following the emergence of Harold Pinter, John Osborne and other notable British playwrights, Noël Coward’s world of the affluent upper middle classes must have felt anachronistic. Yet it was in that year that Suite in Three Keys, the writer’s trilogy of plays, premiered in the West End. Now, over half a century later, director Tom Littler invites us to immerse ourselves for around five hours among Coward’s people and assess whether the plays continue to stand the test of time.

Littler’s revival is a three for the price of two offer, comprising a double bill of the shorter plays and a single production of the longer one. The plays are linked by the same setting, a lakeside hotel suite in Switzerland. Felix (Steffan Rizzi), a genial room service waiter, is a further link and he also entertains us at intervals with music, including 60s American songs sung in Italian. The Orange Tree’s in-the-round configuration gives a fly-on-the-wall feel, which is perfect for the plays.

The double bill begins with Shadows of the Evening, a melancholic piece in which Coward could well be contemplating his own mortality. When George (Stephen Boxer) is diagnosed as terminally ill, his partner, Linda (Tara Fitzgerald) panics and asks Anne (Emma Fielding), the wife that he had left 20 years earlier, to fly out and join them. Coward passes on opportunities to draw laughter from bitchiness between the two women and, instead, opts for a rambling light drama which repeatedly drives up blind alleys. If nothing else, the playlet reminds us that there were times in the not too distant past when divorce was a social taboo and when dying patients were not told automatically by their doctors of their condition.

After an interval enlivened by Felix, Come into the Garden, Maud follows. Verner (Boxer) is a rich American who is married to Anna Mary (Fielding), an insufferable social climber. The arrival of Maud (Fitzgerald), a British-born Italian princess, brings disarray as Coward revels in differences between European and American cultures, one obsessed by social status and the other by money. Fielding has enormous fun as the ghastly Anna Mary, her blue-rinsed bouffant hairstyle giving her the look of an early prototype for Marge Simpson. Fitzgerald also excels as the mischievous temptress who sets her sights on driving a wedge between the couple and giving Anna Mary the comeuppance that Coward clearly believes she deserves.

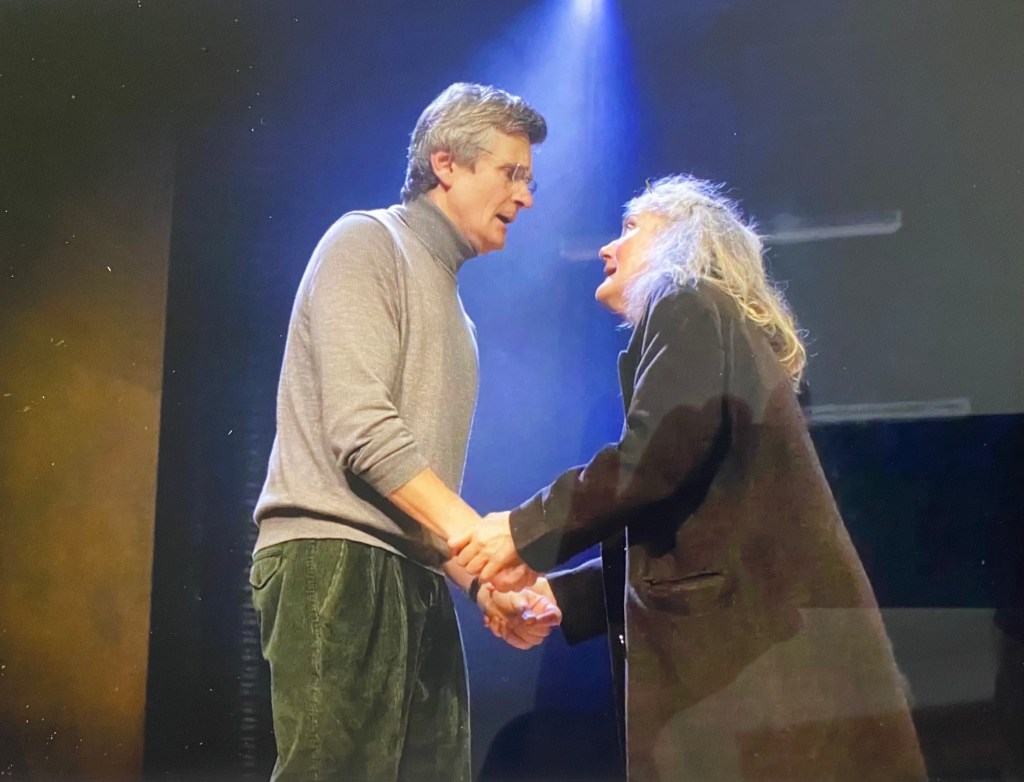

The two-act play, A Song at Twilight, could and arguably should stand alone. Hugo (Boxer) is an eminent writer who lives with his wife of 20 years, the dullish and dutiful Hilda (Fielding). Unexpectedly, he receives a visit from Carlotta (Fitzgerald), a mediocre British actress who had, briefly, been his lover many years earlier. But what does she want? The first act builds slowly, climaxing with the revelation that Hugo had once had a male lover.

Coward is most commonly associated with breezy comedies, but, here, he adopts a style of high drama similar to the works of his contemporary, Terence Rattigan. There are too many coincidences for us not to connect Hugo to Coward himself and, during blazing second act exchanges in which Boxer and Fitzgerald are both magnificent, the writer seems to be challenging himself over a lifetime of deception. Written on the eve of momentous changes in British laws relating to homosexuality, the play feels highly significant and deeply personal.

The sense of daring that flavours much of the writer’s theatre work survives and thrives in these late plays. As a whole, Suite in Three Keys is uneven, but its flaws are by far outweighed by its strengths.

Performance date: 5 June 2024